Read more about Sabina and her work.

Interview with Sabina Myers

Victorian Opera’s Content Producer, Evan Lawson, chats with costume designer Sabina Myers ahead of the season of Shostakovich’s Melbourne, Cheremushki.

Why should someone attend Melbourne, Cheremushki?

If the words “1950s soviet musical comedy” make you wonder what that might sound like, there’s your first reason to come along – it’s undoubtedly strange and entertaining.

In 1959 before the work premiered, Shostakovich, the composer, famously wrote to a friend:

“If you have any thoughts of coming to the first night, I advise you to think again. It is not worth spending time to feast your eyes and ears on my disgrace. Boring, unimaginative, stupid. This is, in confidence, all I have to tell you.”

You might be thinking that this isn’t a very good endorsement, but on the contrary I have to tell you that the work is highly imaginative, and if there are moments of stupidity it’s only because it reflects both the best and worst of humanity. To say too much would be to ruin several surprises, but I can promise you will not be bored.

Melbourne takes centre stage in this production but is depicted in an unexpected way. Tell us about this depiction and how it is explored through the costume design.

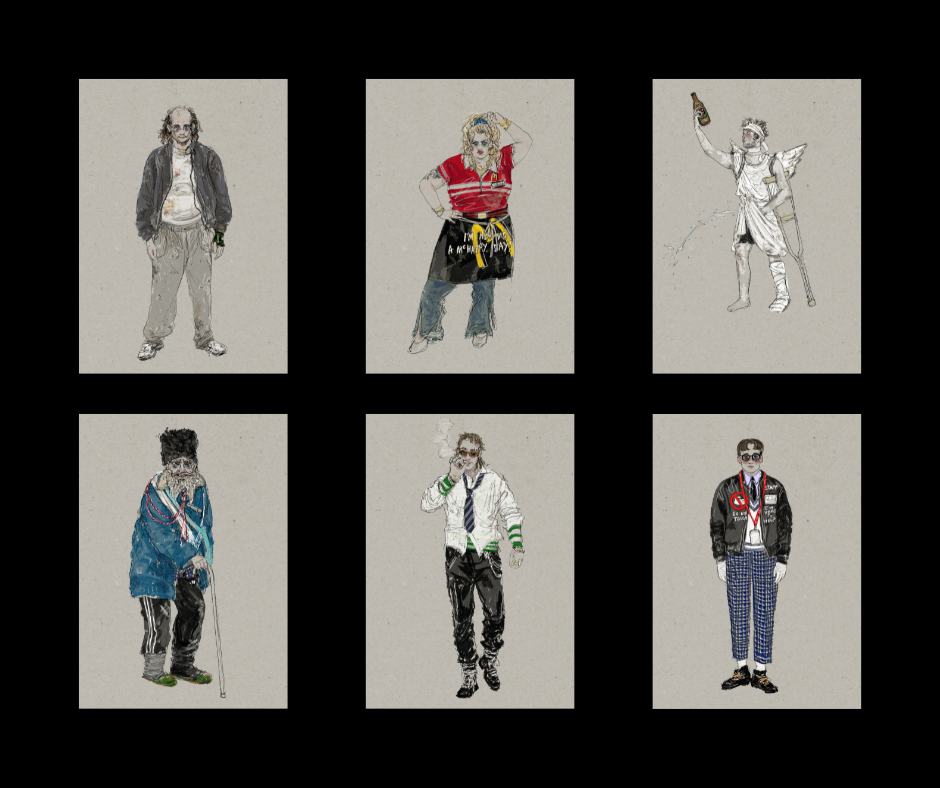

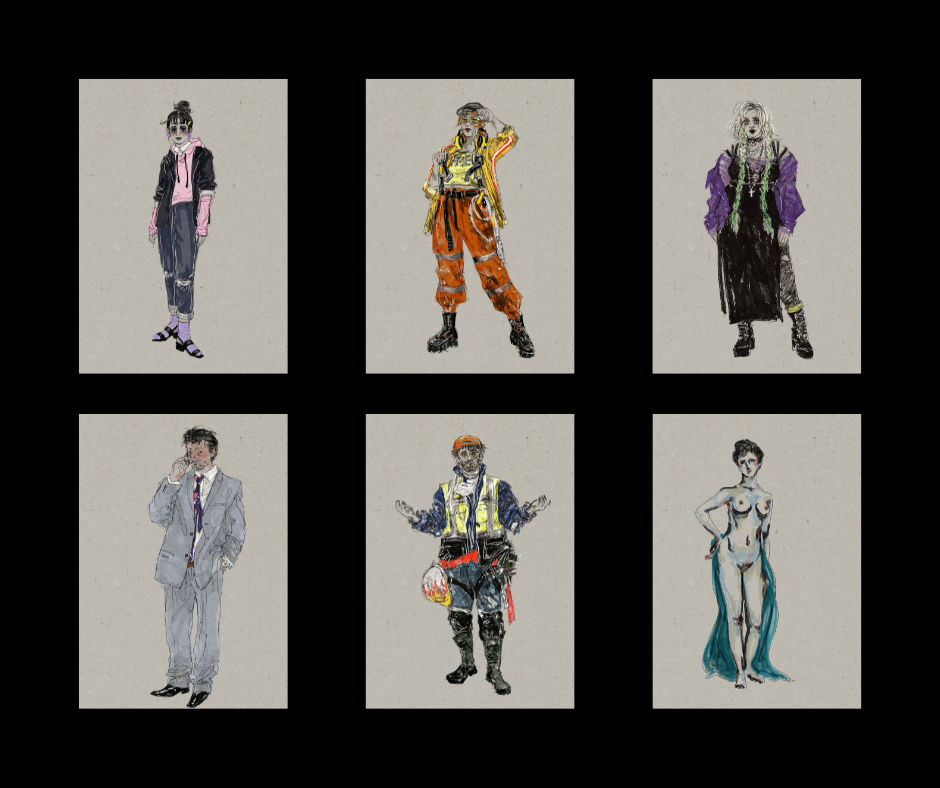

We’ve been describing Cheremushki fundamentally as a ‘dark comedy’. It’s a vision of Melbourne-Naarm that is full of recognisable sights, but there’s a very theatrical, sort of gothic storytelling to it. iPhones, punk t-shirts and high-vis workwear meet operatic makeup and staging, and I hope you’ll find it compelling to see these familiar things in a new and heightened light.

How have you adapted a work that is about Soviet era Moscow in the late 50’s to contemporary Melbourne-Naarm?

You’d think it would be quite a jump to transpose the setting across time and space in this way, but the great thing about works like ‘Cheremushki’ (being fundamentally about people), is that people are the same in every country and every time, just with a different hat on.

A chauffeur becomes an Uber driver, an estate manager becomes a landlord, and some things don’t change at all because construction workers, scheming bureaucrats and young people struggling to earn a dime are timeless fixtures in every big city that has ever existed.

Tell us about your experience with Melbourne-Naarm. Has that shaped your vision for this show in any way?

I’m currently based in Sydney-Warrane, but I’ve also lived in Melbourne-Naarm in the past and this city has it’s own distinct character. People dress in a different way here – it’s more layered, maybe more idiosyncratic. There’s a grit and texture to the cityscape and the architecture, a lot of layers of history and a bit of a grungy, rebellious spirit. I love that about this place and it’s had a big influence on the style of the show.

This production is commenting on the current housing crisis. Some people might think it a strange topic for an opera. What is your response to this idea?

It’s true that when people think about opera the first things to spring to mind might be epic love stories, or ancient myths, but productions like this show how diverse the medium really is. Shostakovich was commenting on the housing situation in Moscow in the 50s, using his artform to reflect something of his own contemporary world, and so we want to do the same – no topic is off-limits. The current housing crisis in Australia is nothing to joke about, but don’t let the fact that this opera is a comedy turn you off. Under the eccentric music and weird dialogue, a cast of very real and loveable characters are just trying to make lives for themselves in a city that won’t make space for them, and I think that deserves an opera just as much as any other story.

As this production is part of the VO Emerges undertaking–that is, productions made by emerging and early career artists–does that change your approach to the work in any way? Do you find that your ideas vary because of the experience of the cast?

Having a relatively young cast for this production is one of its strengths. Often in opera, we might be dressing more seasoned performers as young characters, and it can be difficult to make that feel authentic. But in this case we can tell a story about young, contemporary, urban people with a cast who are exactly that – I think it’s a really exciting opportunity.

How are you responding to Dimitri Shostakovich’s amazing music in this piece?

The music is frankly quite mad, cheerful and upbeat to the point of exaggeration. It creates an amazing opportunity for contrast – we can utilise much darker and grungier aesthetics in the set and costume design because we have the music there as a counterpoint, and the juxtaposition lends a satirical air to certain scenes that’s a lot of fun.

Tell us about working with director Constantine Costi.

Con and I have worked together on a number of operas now, and I always enjoy coming back to this partnership. He’s someone who isn’t worried about risk-taking, and is such a great collaborator. I think he and I are both very interested in character-building and digging into the quirks of what makes people weird and interesting.

Is this an opera that someone could bring a friend to? A friend who has never been to the opera before? Why so?

Absolutely. This is a modern show, both in terms of our production’s treatment of it, and its comparatively recent composition. For a friend who perhaps doesn’t relate to 19th century opera, but likes theatre or musicals (or even just off-beat TV comedy a-la ‘The Mighty Boosh’) this could be just the ticket. Then, having hooked them in with this oddball production, you can pull a classic bait-and-switch, and drag them to see some Puccini next time.