Interview with Lindy Hume

Mozart’s first great masterpiece, Idomeneo, forms a key part of the operatic repertoire, but is perhaps not as widely known as his blockbuster works The Magic Flute, The Marriage of Figaro, Cosi Fan Tutte and Don Giovanni.

The music for this brilliant early work, written when Mozart was only 25, is full of gorgeous melodies, dramatic chorus scenes and all the intrigue you would expect from an opera of the 18th century set in ancient Crete.

In the lead-up to the full production of this work by Victorian Opera, we sat down with the director, Lindy Hume, about her vision for this incredible production.

Tell us about your involvement with Victorian Opera in 2023.

I’m directing the new co-production of Mozart’s Idomeneo for Victorian Opera and Opera Australia. Exciting!

Tell us about your vision for the brilliant Mozart opera, Idomeneo.

Mozart’s Idomeneo brings together mighty forces and epic themes. At its heart, expressed with an empathy that betrays the composer’s own filial torment, is the troubled yet tender relationship between a father and son. Drawing on the famed mythology of the Trojan War, Idomeneo locks a God (Neptune) and a mortal King in battle and unleashes the magnificence and terror of the natural world. At the work’s deep core, we glimpse a monstrous vision: a dark, threatening presence, or void. Then, in a stunning reversal at the end, hope is rewarded with a bright new dawn.

The sea and all the elements of nature surround the ancient island of Crete, animating the Gods who protect or threaten it. The characters in Idomeneo sing again and again of the winds, skies, the forest and horizon. For this reason, finding a way to locate this work in the natural world has been a key to telling this story. In this quest I am grateful and thrilled to be working with a team of extraordinary Australian artists including the Tasmanian filmmaker Catherine Pettman (Rummin Productions) and video designer David Bergman who have created an epic visual language in which the wild and timeless landscapes of lutruwita Tasmania stand in for Ancient Crete.

One fascinating aspect of this production is the set design by Michael Yeargan. Tell us about Michael and how this already existing design has come into this new production.

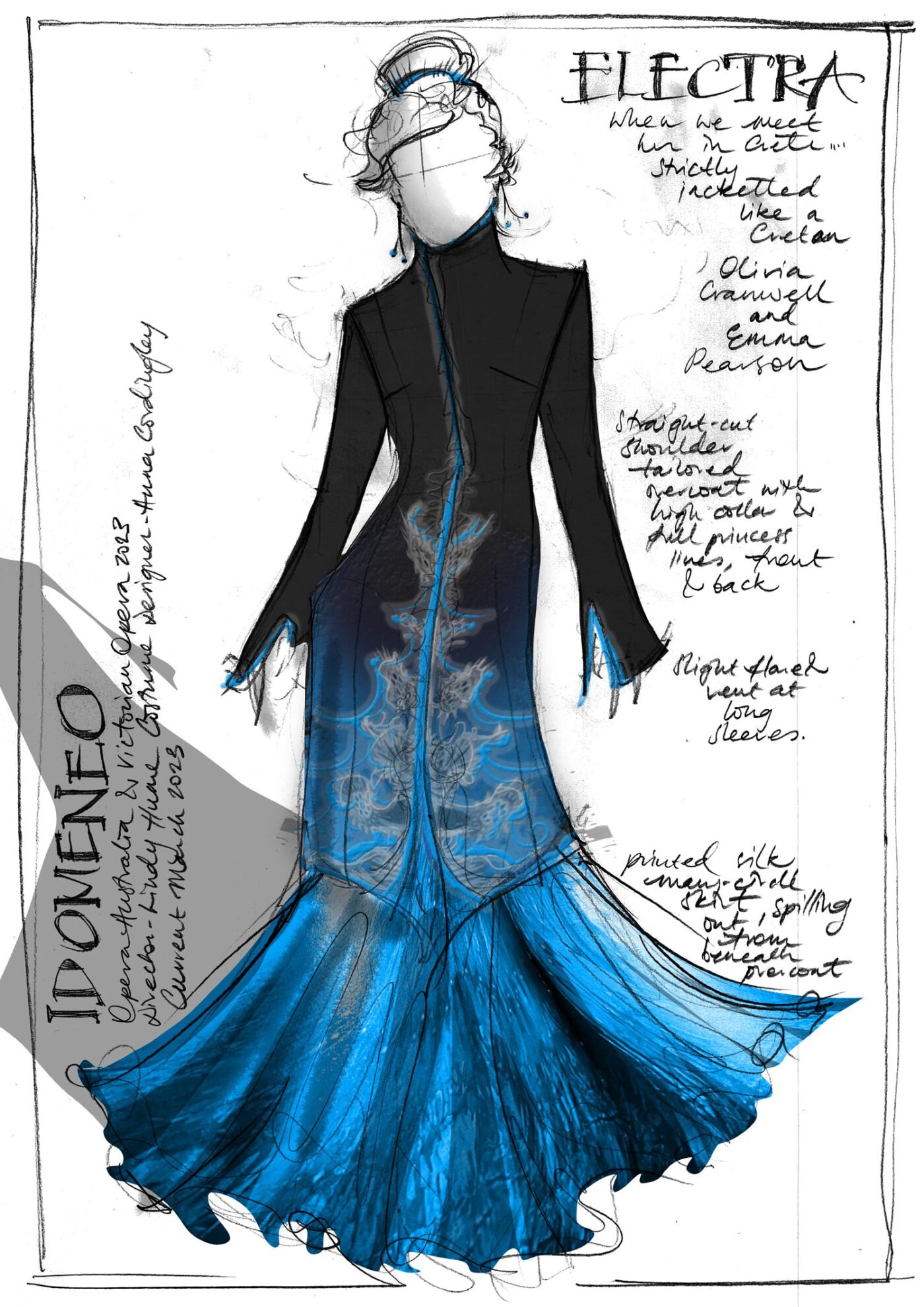

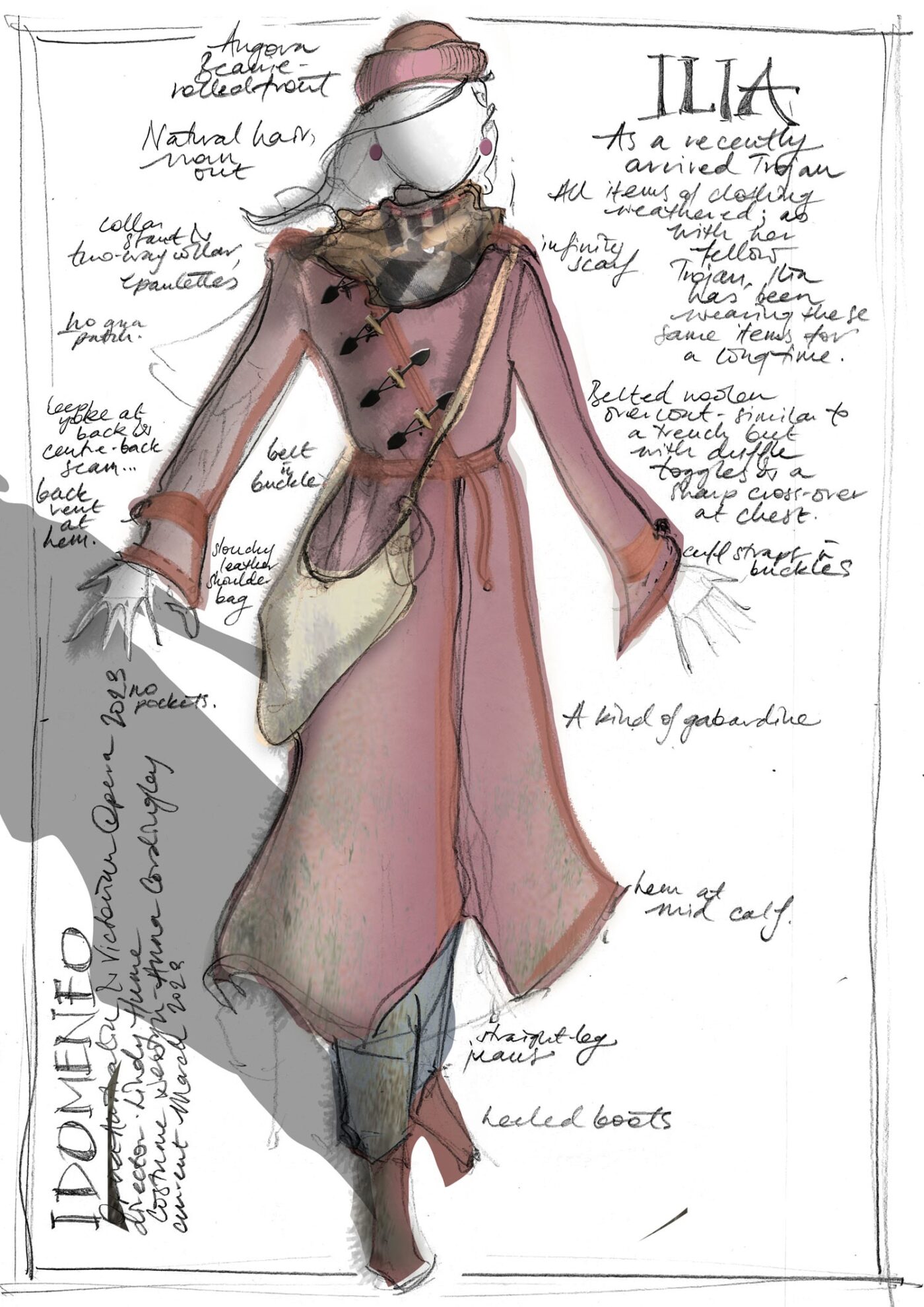

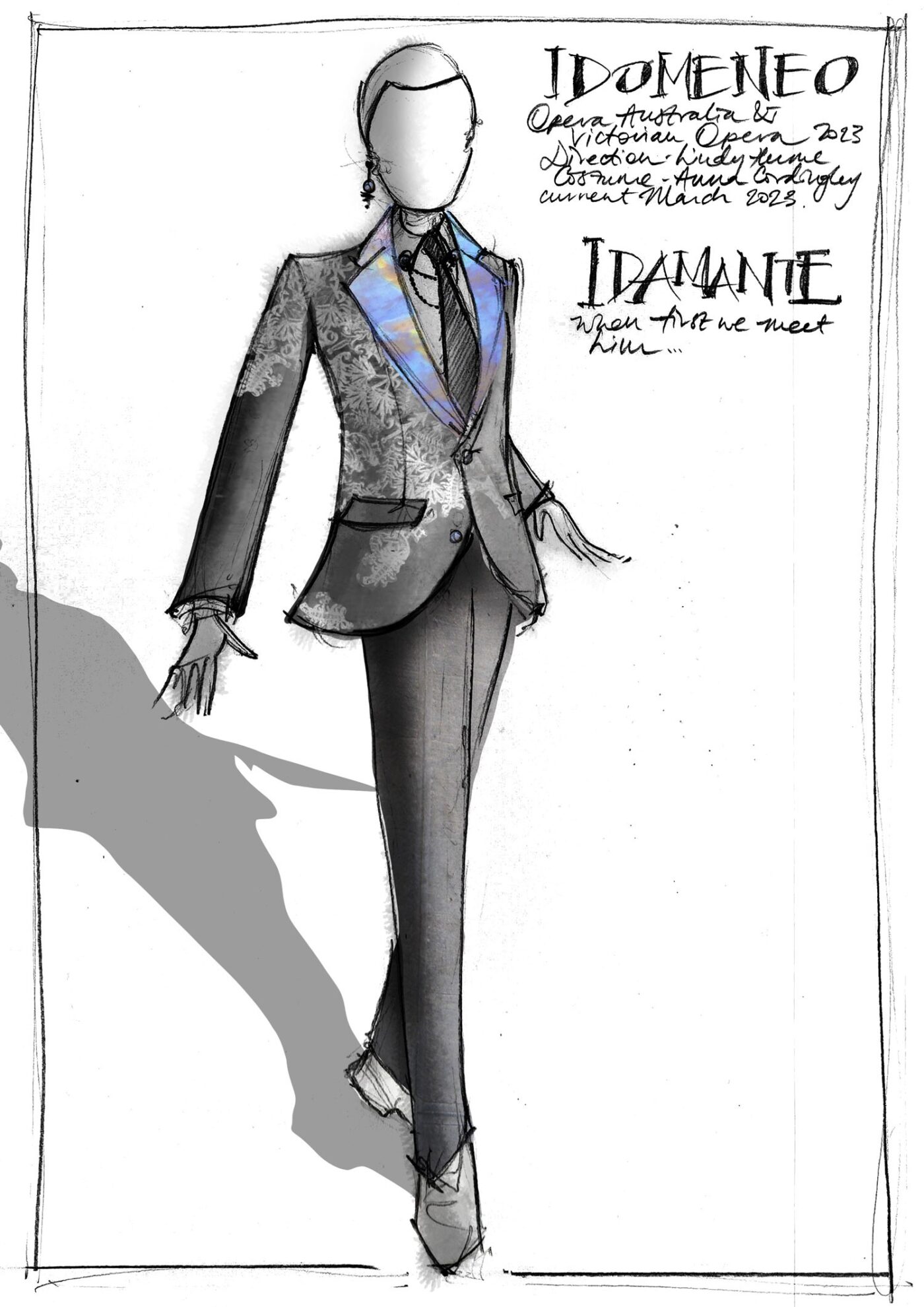

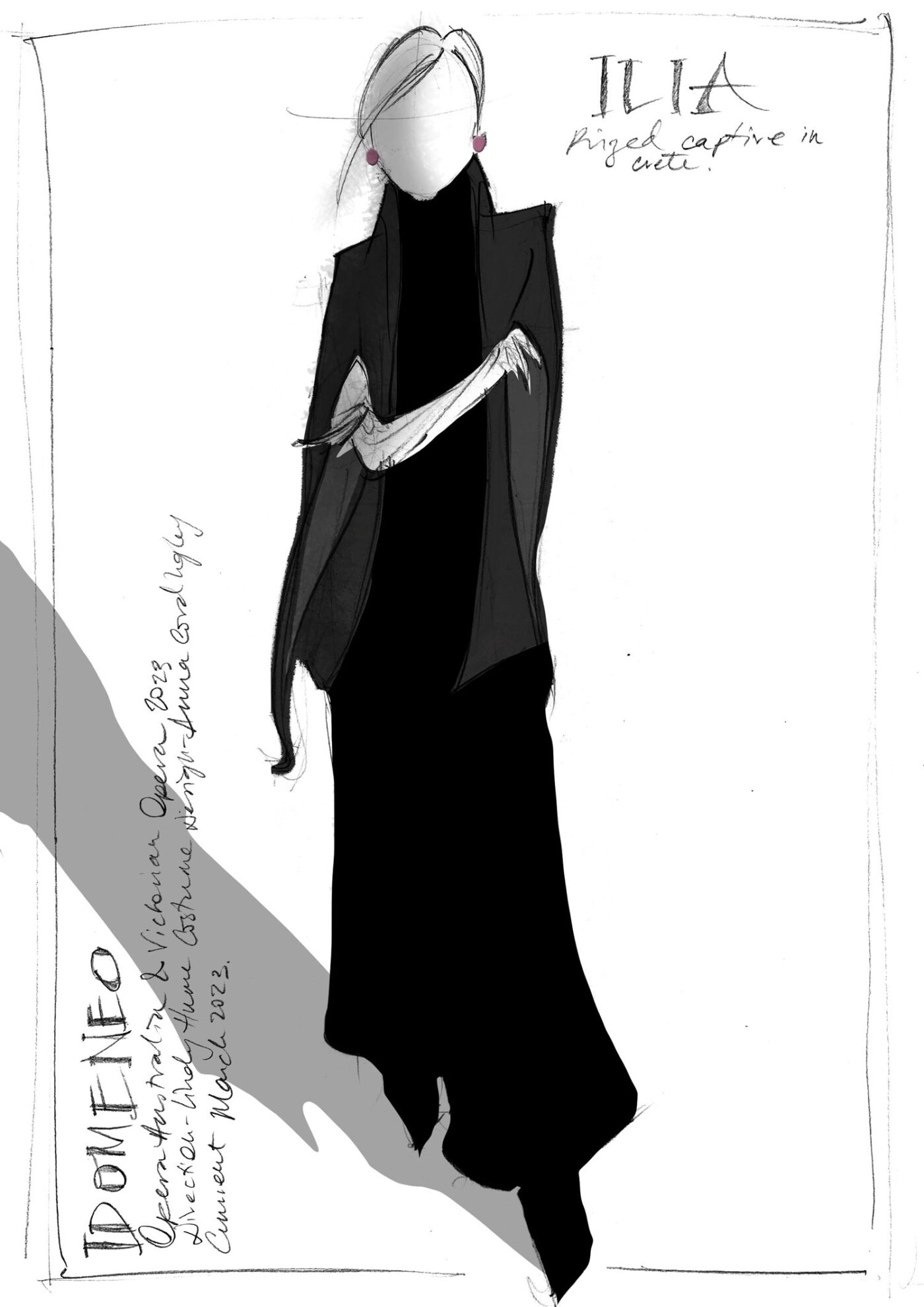

Michael Yeargan is an eminent American theatre designer whose elegant, beautifully proportioned 1989 set for Massenet’s Werther we’re repurposing as the basis for this production. The wonderful Australian designers Richard Roberts (set), Anna Cordingly (costumes), and lighting designer Verity Hampson are working on both productions, to create fresh new ways of reimagining Yeargen’s original set. We’re delighted that Michael has given his blessing to use his set for this project.

David Bergman’s work is well known from the recent Australian tour of The Picture of Dorian Gray. Video and projected images are being used more and more in opera, tell us about David’s work in Idomeneo and how you have included projected images in the world of Idomeneo.

Dave and I first worked together on A Winter’s Journey for Musica Viva, where we wrapped Fred Williams’ landscapes around Allan Clayton’s extraordinary performance of Schubert’s song cycle. When Idomeneo came up, and Michael Yeargen’s white room, I knew it would be exciting to work with Dave again on a larger scale, with sea-images and images from nature this time.

There is no Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI) used in this production. The projections that wrap the three walls of Michael Yeargen’s white room are real images of the wild and peaceful seas, skies, cliffs, kelp, sea foam, forests and albatrosses captured by Rummin Productions on locations across lutruwita Tasmania. These are digitally reworked, colour-enhanced, timed and mapped to our scenic requirements and synchronised with Mozart’s score by David Bergman. While waves, skies and rocks are easily recognised, audiences might be surprised to know that the Act 2 sea-monster is a drone image of a kelp island floating on the Tasman Sea, Idomeneo is pursued in his Act 2 aria by a negative image of a wave creeping along the sand, while the swirling red rage engulfing Elettra in Act 3 is sea foam, digitally coloured and slowed down to surge with her music.

This is the first time Victorian Opera and Opera Australia have collaborated on a production. As an artist who has worked with both companies, tell us why these sorts of collaborations are important and why this sort of collaboration is good for the Australian opera community.

Creative collaborations are the only way forward for opera. It’s an expensive artform because it brings so many large forces together, so the more companies can work together to reach audiences the better. It’s especially important for the national company to work closely with the state companies, to be part of the broader arts ecology, to understand the diversity of opera in Australia and help it flourish. Conversely, it’s important for Victorian Opera to create productions that are ambitious and progressive in terms of theatre-making. Collaborating with OA to share creative resources and upscale production values, as we’re doing with Idomeneo, is a way of expanding Victorian Opera’s reach. Many years ago, Opera Australia and the Victorian State Opera would collaborate regularly, so it’s good to see that happening again.

What are some of your favourite operas or musicals, and why?

I adore Mozart and come into Idomeneo straight from directing Cosi Fan Tutte for New Zealand Opera. I’ve been lucky enough to direct all three great Mozart/Da Ponte operas (Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro and Cosi Fan Tutte) over the last 5 years, so I feel very fortunate. Apart from Mozart, my favourite composer as a director is Handel – he’s such a theatre animal. I’ve directed 8 or so Handel operas including Alcina, Theodora and Orlando here in Australia, Radamisto in Halle and Tolomeo in Belgium but I also love Gluck’s Iphigenie en Tauride – I’m an Enlightenment fan! I’ve probably directed way too much Rossini, but I do love directing comedy, and yes, I’d love to direct musicals too!

You have had a distinguished career in opera. Tell us about some of your career highlights.

I’ve been very fortunate to work regularly for companies in America, Europe, the UK and NZ as well as Australia, and I’ve had some ‘pinch me’ moments directing in places like Stockholm’s Royal Opera House (La Cenerentola) and Berlin’s Staatsoper Unter den Linden (La Bohéme). I’ve commissioned and directed several world premieres, which is always exciting, and I’ve led four international arts festivals and four opera companies. But my great passion is the creative landscape in regional Australia, which is what my PhD is about. I’m very proud of that academic achievement, as I left school at 16. As I get older, more than anything it’s about the people I work with. I seek collaborations with like-minded artists who are interested in being adventurous and exploring new things. The Idomeneo team is a great example of that.

Do you have any recommendations for other artists wanting to follow similar career successes as you?

Just go for it, but you must put in the work. I was an assistant director for 8 years learning the ropes of working with choruses and singers and lots of different repertoire before I got my break. So, I was really ready to start directing, but it was another 5 years or so before I actually felt I could call myself a director, and another 5 years of learning from mistakes and being uncertain to gain confidence in my ideas.

How did you first get into directing?

Working with Opera Australia as a dancer I could see all the micro-steps in the hierarchy to becoming a director, so I spent 8 years as an assistant director, some of it unpaid, to learn the craft and organisation part of things, how to move choruses, how to work with singers, how to schedule etc. The art part came much later.

You’re taking your friend to the opera for the first time. What opera do you take them to and why?

Depends on the friend. But Mozart’s Don Giovanni is pretty thrilling – if the acting and singing is good, and there’s lots of moral light and shade to discuss afterwards.

By Evan Lawson.