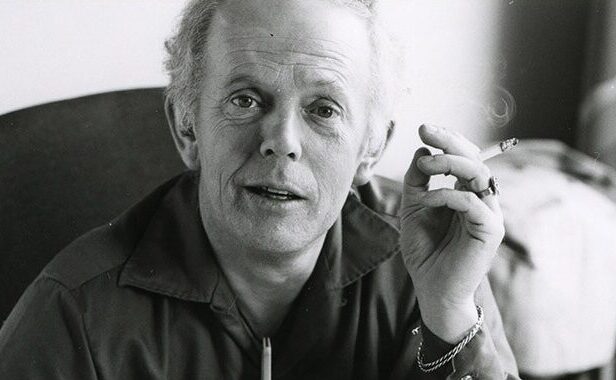

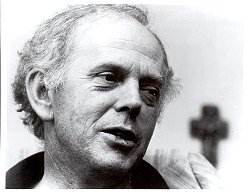

Malcolm Williamson: the forgotten queer legacy of Australia’s most outrageous composer

Even Australia’s most astute theatre enthusiasts might have a hard time recognising the name Malcolm Williamson. It’s a shame – Williamson was arguably Australia’s most successful composer, acutely eccentric, and unapologetically queer.

Williamson (1931-2003) is the composer behind Victorian Opera’s off-the-wall production of English Eccentrics, as well as a ream of symphonies, stage works, chamber, choral and religious music, and even film scores. Over his lifetime he produced an astonishing 250 works, including 13 operas, earning him the label of “the most commissioned composer of his generation”.

But by the time of his death in 2003, he was all but forgotten, especially in his homeland of Australia. There is no single reason why, only a few vague speculations.

One is that Australians never took to Williamson’s work because they resented him for nurturing his talents in the UK, much like many other Australian creatives who moved to London after World War II. Or perhaps it’s that Williamson missed a critical deadline for completing a symphony for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, an error that led him to be apparently cold-shouldered by the music establishment. Most likely, though, it’s that we simply have short memories amid a culture that values newness, and that his music’s eclectic style-switching often made for a challenging, though rewarding, listen.

So as Australia’s first ever professional performance of English Eccentrics gets underway, let’s look back at the hidden legacy of the country’s biggest musical export (before Kylie Minogue).

Out and proud

Williamson was born in Sydney in 1931 and fell in love with instruments and music composition from a young age. The earliest surviving composition was a piano piece he wrote for his grandmother’s birthday at age ten, entitled the “Great Lady Waltz”.

Looking to further his career opportunities abroad, Williamson settled permanently in the UK in 1953. From there, his career blossomed. In 1975 he became the first Australian to be appointed Master of the Queen’s Music, which means he was responsible for developing music for weddings, coronations, funerals and other prestigious royal events.

Despite his closeness to the British monarchy, Williamson never shied away from his sexuality. Once, for example, Williamson allegedly attended a royal event wearing a Jewish skullcap, a large pectoral cross around his neck and a badge that declared “I Am Gay”.

This is remarkable when you consider that homosexuals were heavily policed and discriminated against back then, even after the UK passed its 1967 Sexual Offences Act which (only partly) decriminalised homosexuality.

As human rights campaigner and journalist Peter Tatchell writes in The Guardian: “Not only was homosexuality only partly decriminalised by the 1967 act, but the remaining anti-gay laws were policed more aggressively than before by a state that opposed gay acceptance and equality.”

In the late 1950s, Williamson began a year-long romance with a Brazilian man named Lorenzo. Williamson dedicated his organ score – Fon Amoris (Fount of Love) – to Lorenzo, which went on to become one of his first critically acclaimed works. Their relationship ended in 1958 when he met Dolores Daniel, with whom he married in 1960 for 15 years, and had three children.

Daniel, an American, had a Jewish background. Williamson was brought up Protestant, before becoming a devout Catholic. Williamson said this amalgamation of religious connections heavily inspired his music, such as his Seventh Symphony.

Gossip and Royalty

While Williamson’s music was undeniably popular in the UK, his career was marred by rumours about alcoholism, accusations of poor hygiene and working difficulties. According to Williamson’s biography (Malcolm Williamson: A Mischievous Muse (2008)), the years married to Daniel were filled with music production, but fraught with alcohol abuse and erratic behaviour that cracked chinks in his reputation.

In 2016 the late opera critic Michael Tanner remembered his “bizarre, not to say traumatic” experience meeting Williamson for first time in The Spectator. He wrote:

“I have never met a person so consumed with self-hatred, so evidently able — if he so chose, in the small gaps between fits of drunken incoherence — to be charming, amusing, gossipy and even wise, and so evidently at a stage where there was nothing even the most sympathetic listener could do to help. Any compliment was treated as a spiteful taunt, any attempt at reassurance as a shallow and futile gesture, any suggestion that we might talk about anything other than his gifts, his torments, his deep Catholic faith, an impertinence.”

Still, it was during this turbulent period that he was appointed the new Master of the Queen’s Music. Though, critics speculated that the royal invitation was actually meant for Malcolm Arnold, a more esteemed composer at the time, and that the Royal Family simply chose “the wrong Malcolm” by mistake.

In any case, he remained in this role for the rest of his life, despite behaving like a bit of a rockstar. His eccentricities (for instance, apparently meeting with Queen Elizabeth II wearing silly hats or outrageous outfits), alcoholism, and missed deadline for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in 1977 meant he was never again asked to contribute work for major events.

Add to this a very public divorce from Dolores Daniel before entering another same-sex relationship with organist and publisher Simon Campion, and it may also explain why Williamson wasn’t knighted – the first Master of the Queen’s Music not to be in more than 100 years.

But it was with Simon Campion that Williamson’s life seemed to find more periods of steadier footing. The pair were together for 30 years, until Williamson’s death in 2003.

Campion travelled with Williamson, often performed with him and, crucially, helped with notating, orchestrating, publishing and promoting his compositions. Without Campion’s dedication – even long after Williamson’s death – much more of the composer’s work may have vanished entirely.

A mixed legacy

For those who remember his work, Malcolm Williamson’s eccentricities came to define his legacy. But beyond the gossip is a brilliant composer, one with strong and varied interests, particularly in humanitarian issues such as the rights of Indigenous people, children, and disabled people.

For example, Williamson composed several works for children, including a series of ten “cassations” – innovative mini-operas for musically untrained children that involved audience participation. These have been considered an extremely effective music therapy technique with physically and intellectually disabled children.

Some cassations were political. In one of few works directly relating to Australia, Williamson’s The Glitter Gang (1973-74) explores how European settlers treated Indigenous people. University of Tasmania musicology lecturer Carolyn Philpott calls The Glitter Gang “a powerful statement on behalf of Australia’s Indigenous population and it is directed at arguably the most influential audience for initiating change in Australia’s future; the country’s children”.

A recurring theme in his compositions was the idea of “outsiders”. Or, as Williamson called the characters in English Eccentrics, people who are all “ultimately unacceptable to others”.

Williamson, too, was an outsider in mainstream society. He was queer at a time when it was deemed unacceptable. He was an Australian in England, perhaps feeling like he belonged to neither country. Philpott puts it best:

“In many ways, the sheer diversity of his output […] demonstrates his commitment to composing music that was accessible and useful to a wide audience and also reveals his personal desire, as an outsider from society, to gain acceptance.”

Today, however many lingering rumours about Williamson’s behaviour are factual or embellished is anyone’s guess. But a critical truth endures: Malcolm Williamson and his music deserve to be remembered.

Anthea Batsakis, Victorian Opera Content Editor